Learn With Jermaine—Subscribe Now!

I share what I learn each day about entrepreneurship—from a biography or my own experience. Always a 2-min read or less.

Posts on

Books

New Books Added: Twitter’s Origin Story, and How to Identify Your Unique Ability

In 2024, I challenged myself to accelerate my learning by reading a book (usually a biography) a week. To date, I’ve done it for 77 consecutive weeks. I wanted to share what I was reading and also keep track for myself, which was difficult (see here), so I created a Library section on this site. I added to it all the books I’ve read since my book-a-week habit began in March 2024, and I’ve committed to adding my latest read to the Library every Sunday (see the latest here).

That left the books I’d read before 2024 unshared and untracked. I set a goal to add my old reading to the Library over time. It began with a Memorial Day Challenge to add five books (see here) and continued by challenging myself to add two books every weekend until my backlog is gone. This past weekend was my thirteenth weekend, and I added two more books:

- Unique Ability by Catherine Nomura, Julia Waller, and Shannon Waller

- Hatching Twitter by Nick Bilton

That’s the latest update on my weekend goal. I hope that sharing these books will be of value.

This Week’s Book: The Real Cause of Every Tech Bubble

A few months ago, I was listening to The Slow Hunch podcast, on which the founders of the venture capital firm Union Square Ventures (USV) were interviewed. Fred Wilson and Brad Burnham are the founding partners; they shared stories of founding the firm and notable investments such as Twitter, Etsy, Cloudflare, and Coinbase.

Burnham mentioned a framework they used to develop their initial investment strategy. Where he and Wilson thought they were in the period’s technology cycle played a big role in their strategy. It led them to focus on investing in the application layer of the internet because, they realized, the infrastructure phase was behind them. They got this framework from a book Burnham had read. It had a profound impact on him and positioned USV to become one of the top investment firms by identifying the right founders and companies given their understanding of the technology cycle. You can listen to the sections of the interview where Brad talks about the book and how they used it here and here.

This piqued my interest and led to my booking that book, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital, by the Venezuelan economist Carlota Perez. The book is a blend of a history and a framework. It describes a way of thinking about cycles created by new technology and financial capital and analyzes the five major technology revolutions over the last 250 years and their implications for society: the industrial revolution; steam and railways; steel, electricity, and heavy engineering; oil, cars, and mass production; and information technology and telecommunications.

The core premise of this book is that the combination of new technology and financial capital applied to it creates a technology revolution that leads to speculative bubbles.

According to Perez, each technology cycle lasts roughly 50 years and follows a consistent evolution through three phases:

- Installation. New technology is created, and infrastructure is created to support it.

- Turning point. Speculators’ unrealistic expectations related to the new technology cause a recession or financial crisis.

- Deployment. New technology is distributed widely across society and is accepted, with new rules and regulations being implemented to avoid future crashes.

The book dives deep into the economic and societal impact of each phase, which I found very useful.

Anyone interested in understanding how long technology cycles work, how capital and new technology complement each other, or how speculative technology bubbles work should consider giving Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital a read. It’s dense and full of lots of material that will make you stop and think, so it isn’t a casual read. But Perez’s framing is especially helpful to me as I think about the current AI wave and where we likely are in the long AI cycle.

New: How Connected Is Each Book?

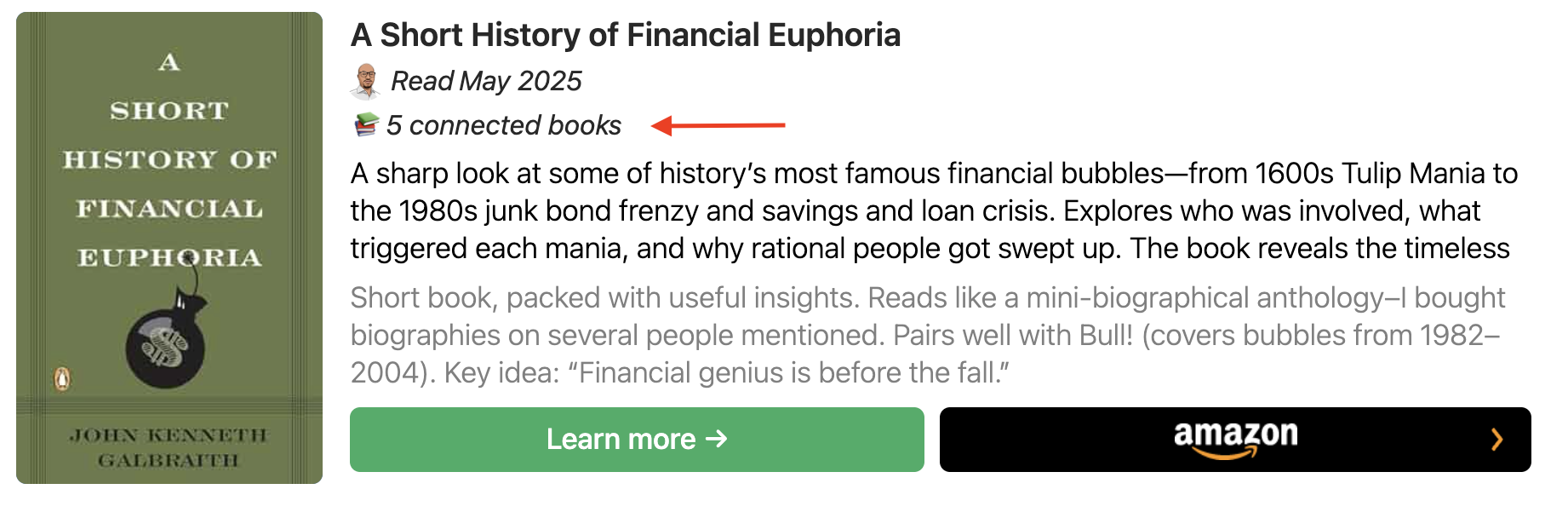

Books are connected to other books, but it’s not easy to see the connections unless you read an entire book. That makes how books are networked, or connected, invisible. The primary way I discover books is seeing them mentioned in another book. I’m constantly making mental connections of ideas, periods, events, or people mentioned in several books. This blog shows the connections between books, but it hasn’t been easy to understand how many connections a book has . . . until now.

Starting today, when you view the Library page, you’ll notice that next to each book is the number of other books in my library with a connection to it. It’s an easy way to quantify a book’s network. If the quantity of connected books is interesting, you can easily see each connection by clicking “Learn more” to see the book’s profile.

I’m excited about this. I haven’t seen anything like it on other blogs. It’s helped me think more deeply about book connections. I hope that understanding how networked a book in my library is will help people find books they find useful.

If you want to see for yourself, check it out:

New Books Added: How to Angel Invest and America’s Biggest Pill Mill

In 2024, I challenged myself to accelerate my learning by reading a book (usually a biography) a week. To date, I’ve done it for 76 consecutive weeks. I wanted to share what I was reading and also keep track for myself, which was difficult (see here), so I created a Library section on this site. I added to it all the books I’ve read since my book-a-week habit began in March 2024, and I’ve committed to adding my latest read to the Library every Sunday (see the latest here).

That left the books I’d read before 2024 unshared and untracked. I set a goal to add my old reading to the Library over time. It began with a Memorial Day Challenge to add five books (see here) and continued by challenging myself to add two books every weekend until my backlog is gone. This past weekend was my twelfth weekend, and I added two more books:

- Angel by Jason Calacanis

- American Pain by John Temple

That’s the latest update on my weekend goal. I hope that sharing these books will be of value.

This Week's Book: 19 Investing Principles from Howard Marks

Last week I shared a framework book, Warren Buffett’s Ground Rules, which details the principles Buffett used to run his partnership, Buffett Partnership Ltd, in his pre–Berkshire Hathaway days. When I read that book, it reminded me that few investors who are active today were also actively investing in the 1960s and 1970s, like Buffett.

Another person who meets those criteria is Howard Marks, cofounder of Oaktree Capital. Marks has written two books, one of which I read twice. So, I decided to read his other book, The Most Important Thing.

This book is a framework book that details the investing principles that Marks has learned over his many decades of investing, many of which led to the outsize success of Oaktree Capital. Each chapter is dedicated to one of the 19 principles and explains it thoroughly. My favorite was the chapter on understanding risk.

This book is a good tool for anyone interested in investing or understanding how public markets work. I enjoy Marks’s writing, and this book didn’t disappoint. I’ll definitely read it periodically as a refresher.

New Books Added: Secrets, Crime, and Venture Capital

In 2024, I challenged myself to accelerate my learning by reading a book (usually a biography) a week. To date, I’ve done it for 75 consecutive weeks. I wanted to share what I was reading and also keep track for myself, which was difficult (see here), so I created a Library section on this site. I added to it all the books I’ve read since my book-a-week habit began in March 2024, and I’ve committed to adding my latest read to the Library every Sunday (see the latest here).

That left the books I’d read before 2024 unshared and untracked. I set a goal to add my old reading to the Library over time. It began with a Memorial Day Challenge to add five books (see here) and continued by challenging myself to add two books every weekend until my backlog is gone. This past weekend was my eleventh weekend, and I added two more books:

- The Mastermind by Evan Ratliff

- Secrets of Sand Hill Road by Scott Kupor

That’s the latest update on my weekend goal. I hope that sharing these books will be of value.

This Week's Book: Warren Buffett’s Playbook Before Berkshire

I’m continuing to lean into my curiosity about the late 1960s through roughly 1982. This was a period of social and economic change. Interest rates were near 20%, and inflation was double digit.

Last week, I shared a biography I read about how Thomas Rowe Price Jr, founder of T. Rowe Price Group, navigated that period. This week, I dug into how Warren Buffett handled it by reading Warren Buffett’s Ground Rules. It was pre-Berkshire Hathaway, so Buffett was managing an investment partnership, Buffett Partnership Ltd. (BPL), and investing other people’s money (his LPs’).

This book isn’t specifically about the period in question. It’s more of a framework that details the principles that governed Buffett’s investments and how he applied them during the years he was actively investing via BPL, 1956 to 1969. The book is unique in that each chapter focuses on a Buffett principle, which is explained and then supported with excerpts from various BPL letters Buffett wrote. It does a great job of explaining his thinking and some of the investments BPL made. It devotes a section to the structure of BPL. It describes the three investing strategies Buffett used at BPL to generate outsize returns: generals (buying generally underpriced securities), workouts (profiting from merger arbitrage), and controls (taking majority ownership to influence a company’s direction).

This book also explains Buffett’s thinking regarding how to navigate the period I’m interested in. I learned that Buffett opted to sit on the sidelines and not invest. In May 1969, he announced that he was closing BPL and would return investors’ money. He went on to send a 17-page letter to his investors in early 1970 about the mechanics of tax-free municipal bonds, which he suggested they invest in. After BPL closed, the stock market experienced a very volatile period with significant declines in several years.

It was great to learn about the early Buffett days, his strategies, and why they worked. It was also eye-opening to see how he sidestepped the period I’m curious about. Anyone interested in BPL or Buffett’s early days should consider reading this book.

Five Years, 110 Books, One Library Project

Every weekend since the Memorial Day Challenge (see here), I’ve been adding all the books I read before 2024 to the Library section of this site. As of this past weekend, I’ve officially added all the books I’ve read from 2020 through today—roughly five years’ worth of reading.

I still need to add books from the years before 2020, and I’ll continue to do that over time. But getting 2020–2025 done felt like a nice milestone. I now have a place where I can go back and see how my reading and learning have evolved over several years (and they’ve evolved a ton!). This project isn’t going to win awards or generate any revenue, but I’ve put a ton of energy into it over the past few months, and I’m proud of how it’s turned out.

As of today, I’ve added a total of 110 books, and I’m excited to add more as I continue learning.

Two Books Added: Financial Crashes and VC Deals

In 2024, I challenged myself to accelerate my learning by reading a book (usually a biography) a week. To date, I’ve done it for 74 consecutive weeks. I wanted to share what I was reading and also keep track for myself, which was difficult (see here), so I created a Library section on this site. I added to it all the books I’ve read since my book-a-week habit began in March 2024, and I’ve committed to adding my latest read to the Library every Sunday (see the latest here).

That left the books I’d read before 2024 unshared and untracked. I set a goal to add my old reading to the Library over time. It began with a Memorial Day Challenge to add five books (see here) and continued with my challenging myself to add two books every weekend until my backlog is gone. This past weekend was my tenth weekend, and I added two more books:

- Manias, Panics, and Crashes by Charles P. Kindleberger and Robert Aliber

- Venture Deals by Brad Feld and Jason Mendelson

That’s the latest update on my weekend goal. I hope that sharing these books will be of value.

This Week’s Book: How T. Rowe Price Outsmarted ’70s Inflation

I’m increasingly curious about the late 1960s through roughly 1982. Inflation was double digits. Interest rates were right at 20%. Lots of social and economic change was going on.

I’ve been digging into this period for the last few weeks to understand what happened, why it happened, and what can be learned. This week’s book, T. Rowe Price, is a deeper dive into the time. This biography of Thomas Rowe Price Jr., founder of T. Rowe Price Group is a reread; when I read it before, I noted that Price was ahead of the pack in seeing what was coming in the ’60s and ’70s and positioning himself and his portfolios to sidestep the turmoil.

The book has a chapter dedicated to the period from 1971 to 1982. In that chapter, it details the macro events that Price focused on to understand what was happening and determine what was likely to happen. It also provides perspective on the political climate and discusses how the actions of Richard Nixon and Arthur Burns accelerated inflation. It details how Jimmy Carter appointed Paul Volcker Fed Chairman and the drastic actions he took to get inflation under control. This chapter talks about a lot more and does a great job of describing how the dominoes fell during this period.

Lastly, this book uses Price’s private notes to highlight his thoughts on the trajectories of inflation and monetary policy. Understanding the raw thoughts of someone as they navigated this period was very helpful. It also details the actions he took with his portfolios, why he took those actions, and why his portfolios performed so well.

I’m glad I read this book again. It was even better than the first time because it helped me answer specific questions and fill in the gaps. The chapters covering the 1960s through the early 1980s were exactly what I was looking for and I absorbed more from them the second time around.

Anyone interested in learning more about one of the great investors and entrepreneurs or the changes in the investment landscape from the 1930s through the 1980s might enjoy reading T. Rowe Price.