Billy Wilkerson Part 2: How Addiction Almost Derailed the Big Vision

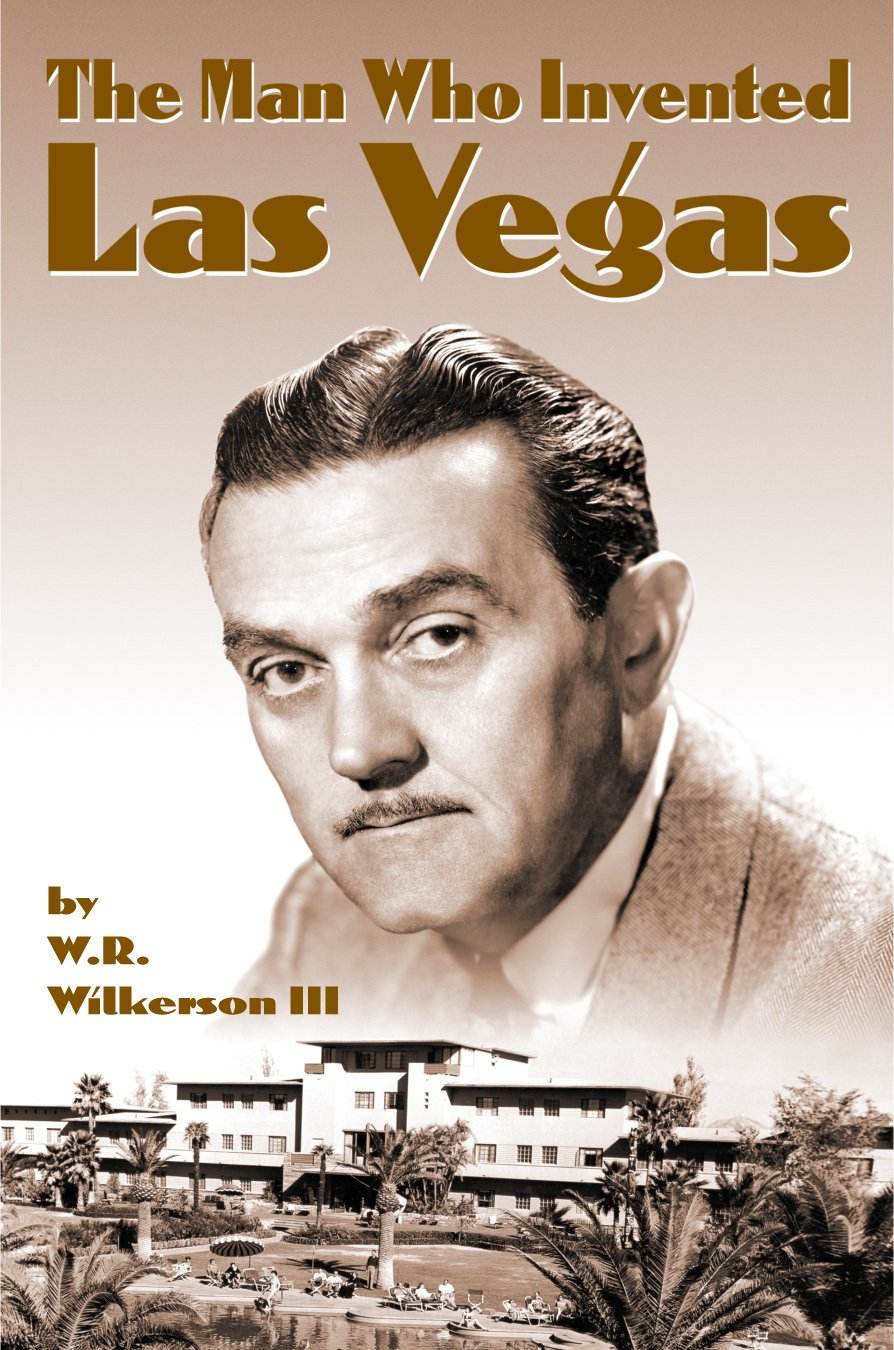

By the end of 1944, William Richard “Billy” Wilkerson sought ways to gamble legally without incurring personal losses. According to the biography of his life, he looked hard at Las Vegas because Nevada was the only state with legal gambling at the time. The extreme desert heat and seclusion initially turned him off, but he realized the location was perfect for limiting distractions to gamblers. In December 1944, he leased the El Rancho Vegas for six months for $50,000, but he had bigger plans. He wanted gambling to be an elegant experience as it was in Europe, not a rustic experience as it was in the few casinos in Las Vegas at that time.

In January 1945, Billy purchased thirty-three acres several miles outside the city for $84,000. People thought he’d made a mistake, but Billy knew he couldn’t get that much land in the town and wanted to avoid competing with existing casinos.

In February, Billy started putting his vision on paper and hired architects. He wanted to build an oasis that would be heaven for gamblers and a relaxing spot for non-gamblers. He envisioned it as a luxurious vacation destination with a casino, showroom, nightclub, hotel, restaurants, health club, and more. He wanted his project to resemble European luxury and rival a Monte Carlo casino, with black-tie evening attire. Billy leaned on his gambling addiction to create the perfect gambling environment—including no windows so gamblers wouldn’t be distracted by sunlight. Most importantly, his project would be the first hotel in the United States to offer air conditioning, making the desert comfortable for the rich and famous patrons he wanted to target. Billy loved birds, so he named his project the Flamingo Hotel after the beautiful pink birds he’d seen on a trip to Florida.

Billy didn’t know how to run a gambling operation, so he hired Gus Greenbaum and Moe Sedway, who were overseeing lucrative gaming operations at the El Cortez Hotel. Both got good at running gambling operations by doing it illegally as bookmakers. They became silent partners and assumed responsibility for gaming, including staffing and permits.

With plans complete, the project was budgeted at $1.2 million, money Billy didn’t have. Bank of America reluctantly agreed to finance $600,000, and Howard Hughes loaned Billy $200,000. Billy decided to gamble with $200,000 to get the rest but lost it all. Frustrated by this and his continuing gambling losses of up to $10,000 a day, Billy erratically bowed out of the project and signed the land deed over to Sedway in September 1945 to settle a debt.

After seeing what Billy had done with Arrowhead Springs, Joseph Schenck believed in his vision for The Flamingo and convinced Billy to keep pursuing the project. Billy listened and bought the land back from Sedway. In November 1945, construction started, but post-war, materials were scarce and expensive, so the inflated costs exceeded Billy’s budget. The project was 33% complete and Billy had $300,000 invested and not enough to finish. He bet $150,000 of his last $200,000 to make quick money to keep the project going. He lost it all. In January 1946, construction was halted.

In February, a well-dressed businessman from the East Coast named G. Harry Rothberg offered Billy a $1 million investment for a 66% stake in his project. Billy would remain the operator and manager, and Rothberg’s investment group would be silent partners. Billy wouldn’t have to put any more of his own money into the project. Billy was intrigued. He didn’t like having partners, but investors who stayed out of the way he could live with. He negotiated to retain 100% ownership of the land and closed the deal.

After Billy received the funds, Sedway and Greenbaum introduced Billy to his new partner, Ben Siegel, better known as Bugsy Siegel. Billy didn’t know it then, but things would never be the same.

Prefer listening? Catch audio versions of these blog posts, with more context added, on Apple Podcasts here or Spotify here!