John H. Johnson Part 4: Professional Success and Personal Tragedy

In 1949, John H. Johnson was doing well. He was a millionaire at 31, and his magazines, Ebony and Negro Digest, were thriving. That wasn’t good enough for John; he feared losing it all. He launched two magazines in 1950 and two in 1951, including JET. JET was a breakout success, selling out its first issue and reaching 300,000 weekly circulation in six months.

According to his autobiography, JET’s and Ebony’s success reduced the circulation of Negro Digest, and John discontinued it in 1951 so he could focus on strengthening his company’s foundation. Cash flow issues, dealing with recessions, expanding the advertising team, and building a solid accounting and finance team all had to be done simultaneously. John recruited talented workers who lacked growth opportunities at large publishing houses. And he set up a system where everyone continuously grew by mastering several skills. Specialists weren’t allowed.

In the 1950s, John created a four-point plan to make Ebony and the Black consumer market integral parts of corporate America’s marketing and advertising plans. He wrote articles in trade publications and provided data to ad agencies and corporations to confirm the spending power of the Black consumer. His strategy worked: advertising dollars increased. However, these new believers, needing staff who understood Black consumers, poached John’s team members.

In 1954, John faced twin headwinds: a series of recessions and a shift away from newsstand sales for magazines. In one month, Ebony’s circulation dropped by 100,000. If Ebony failed, his company would collapse. John shifted the revenue mix to half subscriptions, half newsstand sales and changed the content to reflect the seriousness of what his readers were facing.

After thirteen years of fighting to survive and ten years of publishing Ebony, things finally stabilized. John’s first thirteen years had been hell, but he’d made it. He had 145 employees and a monthly circulation of 2.6 million copies across four magazines. Johnson Publishing was healthy and on solid footing.

With his company running smoothly, John lifted his head and focused outside Johnson Publishing. John and Eunice were ready to start a family but encountered infertility issues. They were rich and successful but couldn’t obtain what they both craved: children and a family. They endured embarrassing and painful exams at the Mayo Clinic, only to learn they both had healthy reproductive systems. Not being able to have children can be a blow to a man’s ego, but John and Eunice investigated adoption for a year and decided it was the best option for them. In June 1965, they adopted a two-week-old son and named him John Harold Johnson Jr. Two years later they adopted a two-week-old girl and named her Linda Eunice Johnson.

The family’s happy times didn’t last. John Jr. began having long bouts of sickness. John and Eunice learned that their son had sickle-cell anemia. They discovered that there was no cure and John Jr. would endure pain and likely die early from the disease. To make matters worse, the adoption agency had forgotten to test John Jr. when he was a baby. The situation changed John. Knowing he had limited time, he traveled less and made being home daily for dinner a priority. He dedicated Sundays to doing fun things with his family. John Jr. lived life to the fullest and was fearless. Sadly, he died in 1981 at 25. John and Eunice were devastated. John kept his son’s office at Johnson Publishing, setting it aside in his memory. And he and Eunice left John Jr.’s bedroom as it was the day he died.

John went on to do many more amazing things. He created Ebony Fashion Fair, which became the largest traveling fashion show in the world. He launched a best-selling cosmetics company and entered the cable, radio, and TV production business. He dabbled in commercial real estate and acquired Supreme Life Insurance Company. And he accomplished all these things in business while serving on numerous corporate boards and having direct relationships with and working with four US presidents.

John’s journey was incredible, and he was a remarkable entrepreneur. His companies had an enormous impact on Black Americans and changed how Blacks and the rest of the United States viewed Black America. That he bootstrapped Johnson Publishing to almost $200 million in annual revenue in the 1980s while owning 100% of the company shows how special the poor boy from Arkansas City was.

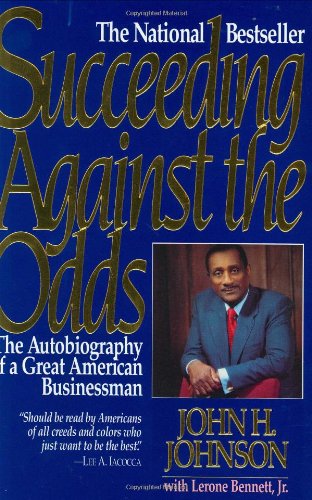

I couldn’t cover everything in John’s autobiography. I picked the things that interested me most, but it contains other great stories and details about his life and journey. It’s worth reading. He shares valuable wisdom he learned along the way.

In my next post, I’ll share my takeaways and insights from his journey and what specific traits made him so successful.

Prefer listening? Catch audio versions of these blog posts, with more context added, on Apple Podcasts here or Spotify here!