Ted Turner Part 5: How to Lose $8 Billion

In 1995, Robert Edward “Ted” Turner III sold his company in a $8 billion deal with Time Warner. After almost twenty years of ownership, his Atlanta Braves won the World Series. And his marriage with Jane Fonda was the “most intense and fulfilling” of all his marriages. Turner was riding high.

According to his autobiography, Turner began adjusting to being an executive at Time Warner. The extravagant sums spent at headquarters while post-merger cuts were being made bothered Turner. The culture was also different. Turner Broadcasting’s strength came from the division heads working together toward the parent’s goals. Timer Warner was a series of fiefdoms that didn’t work together. Turner and Time Warner CEO Jerry Levin worked well together, but they never became friends and didn’t socialize outside work. Regardless, the business was doing well, and by 1997, Ted’s Time Warner stock holdings were worth $3.2 billion.

Part of the reason Time Warner was growing wasn’t obvious at first. But eventually Turner noticed that “dot-coms” were showing up frequently in his sales reports for the cable networks he managed. Start-ups had raised tons of money and spent it with traditional media companies like Time Warner to acquire customers. Turner realized the internet craze was boosting their ad sales.

Time Warner’s business was doing well, but public market investors perceived it as an “old media” company. As a result, they sold Time Warner stock to buy dot-com stocks. Jerry Levine felt pressure from financial media and analysts to do more on the internet to lift the company’s stock price, so he rushed to develop a digital strategy. Around this time, Ted and Jane started having difficulty communicating and started attending counseling sessions as a couple and individually.

AOL founder Steve Case and Jerry Levine met in fall 1999 and began discussing working together. At the time, Time Warner had revenue five times greater than AOL’s, but AOL’s stock market value was twice as large. Then on Friday, January 7, 2000, Levine called Turner and told him they were merging with AOL. The news shocked Turner, who wasn’t aware a deal was in the works.

Ted had a few days to decide whether to vote in favor of the deal at an emergency board meeting and whether to vote his 100 million shares in favor of the deal. He was asked to sign an irrevocable agreement that prevented him from selling shares before the deal closed, which was estimated to take a year. Turner supported the deal, and the $160 billion deal caused a media frenzy when it was announced the following Monday. Time Warner’s stock rose 40% that day, and Turner was worth $10 billion.

A few months later, things took a turn. The stock market tanked and the NASDAQ Composite Index lost a third of its value in a three-week period. AOL’s stock dropped, which made the all-stock deal less appealing. The dot-com crash had begun, and Turner knew AOL wasn’t worth what people thought, but he had no power to protect himself or do anything about it. To make matters worse, Levine informed Turner that post-merger, he would have no responsibilities and no direct reports but would continue receiving his salary. Ted felt that he was being fired. In January 2001, regulators approved the deal to close.

This was a period of extreme difficulty for Turner. He’d lost his job and his wife. His fortune was steadily declining, and insider trading laws prevented him from selling any of his shares. To make matters worse, his two-year-old granddaughter died from a rare genetic disorder. The weight of this all caused severe anxiety, and Turner couldn’t sleep.

Things went from bad to worse. The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks drove the stock market down further and slowed the economy. Jerry Levine and Steve Case were forced to acknowledge to Wall Street that AOL Time Warner would not meet its lofty projections. The stock, which had tanked to $40 months earlier, dropped to $30. Ted’s frustration spilled over, and he pushed Jerry Levine to step down as CEO, which he did in December 2001.

In April 2002, the stock dropped below $20. Ted couldn’t take it anymore and sold $190 million in shares at $18.50 to pay off his bank debt. In July 2002, the stock fell to $13, and then the bottom dropped out when the Washington Post ran a story about accounting irregularities at AOL. The SEC opened an investigation, and the stock dropped to below $9. Turner was in shock. Over two-and-a-half years, Turner’s net worth went from $10 billion to $2 billion. He’d lost $8 billion in 30 months, which was equivalent to losing $10 million every day for two-and-a-half years.

Ted, enraged, forced Steve Case to resign as chairman of the board of directors, which he did in January 2003. In February, Ted resigned as vice chairman of the board. The company was laying off people and selling assets to stabilize itself. Ted found this painful to be part of, and he continued selling his shares. By May 2003, he’d reduced his ownership from 100 million to 7 million shares. That year, he decided not to stand for reelection to the board of directors, and in August 2003, he sold his remaining 7 million shares for $16 each.

The AOL and Time Warner ordeal was extremely stressful for Ted and gave him bouts of anxiety and frustration, but it didn’t stop him. He left the company he’d been with for fifty years, but he was still full of energy that he wanted to put to good use.

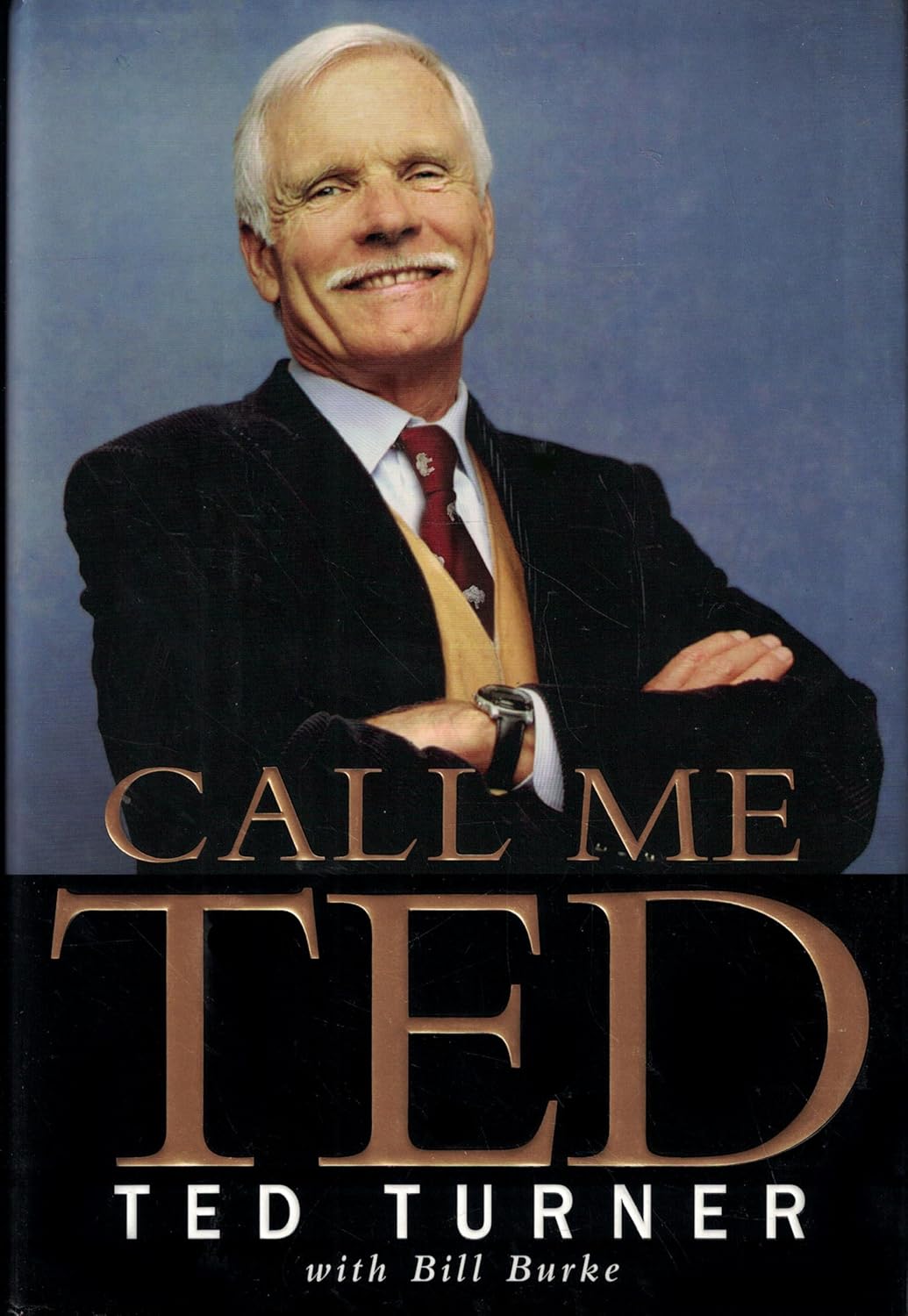

Ted Turner is a remarkable entrepreneur with a colorful personality. His journey was inspirational—he was an outsider entrepreneur who not only thrived but built a massive company. Turner isn’t perfect, and his journey is also full of cautionary tales. Anyone interested in learning more about media, sailing, owning sports teams, ranching, or growth through acquisition will likely enjoy his autobiography.

Prefer listening? Catch audio versions of these blog posts, with more context added, on Apple Podcasts here or Spotify here!