Learn With Jermaine—Subscribe Now!

I share what I learn each day about entrepreneurship—from a biography or my own experience. Always a 2-min read or less.

Posts on

Books

This Week’s Book: 22 Timeless Principles of Marketing

Last week, I read Invested, the autobiography of Charles Schwab, founder of the namesake firm. One of my big takeaways was how well Schwab understood marketing and leveraged it heavily to acquire customers. Marketing and technology were huge differentiators for the company and led to success.

Several months ago, I bought the book The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing by Al Ries and Jack Trout. I decided to read it after learning how critical the market was to Schwab. The book discusses 22 laws that distill marketing to its bare essence in a way non-marketers like me can understand.

Here are the 22 laws:

- Laws of Leadership – It’s better to be first in a category than to have the best product in a category. “Marketing is a battle of perception, not products.”

- Law of the Category – If you can’t be the first person in a category, find a new category you can be first in. Amelia Earhart was the third person to fly over the Atlantic Ocean solo, but she’s remembered as the first woman to accomplish this.

- Law of Mind – It’s better to be first in the prospect’s mind than the first to market with your product. Being first to market with a product is important only because it allows you to be first in the mind of the prospect. “If marketing is a battle of perception, not product, then the mind takes precedence over the marketplace.”

- Law of Perception – Marketing isn’t a battle of products or product quality; it’s a battle of perception. What matters most is the perception of your product in the minds of people. Studying how perceptions are formed in the mind is key.

- Law of Focus – The most powerful concept in marketing is owning a word in the prospect’s mind. You can “burn” your way into a prospect’s mind by narrowing your focus to a single word or concept.

- Law of Exclusivity – Two companies can’t own the same word in a prospect’s mind.

- Law of the Ladder – The marketing strategy you use depends on where you rank on the ladder. If you’re not number one, that’s OK, but your marketing strategy can’t be to market as if you’re number 1. You must own your number 2 position and market accordingly.

- Law of Duality – In the long run, most markets are dominated by two companies.

- Law of Opposite – If you want to own the second rung on the ladder, study the number 1 company. Find its strength and present the customer with the opposite. Don’t try to beat it at its game; try a different angle, try to be different.

- Law of Division – Large categories will, over time, split into subcategories.

- Law of Perspective – The true effects of marketing take place over a long period of time. The short-term effect is often the opposite of the long-term effect. Discounting boosts revenue in the short term but decreases margins and long-term revenue by conditioning customers to buy only when there’s a sale.

- Law of Line Extension – Line extension is taking the brand name of a successful product and applying it to a new product. This seems logical and is irresistible because it’s the easy way to jump-start a new product, but it often doesn’t work.

- Law of Sacrifice – You have to give up something (i.e., you have to focus) to be successful. Being focused allows you to become known for something in the prospect’s mind.

- Law of Attributes – You must have an idea or product attribute that you own and can focus your efforts on. Don’t emulate and try to own attributes that others own, especially the market leader.

- Law of Candor – Admitting a negative about yourself is disarming to your prospect, and they automatically accept it as truth. It opens people’s minds and makes them more receptive to whatever you have to say.

- Law of Singularity – One marketing effort will likely produce the vast majority of your results. This law is similar to the Pareto Principle (i.e., the 80/20 rule).

- Law of Unpredictability – Marketing plans based on predictions about the future will usually fail. You can’t predict the future, so don’t try to predict how your competitors will react or what the future state of your market will be.

- Law of Success – Successful people often become less objective. Success breeds arrogance, and arrogance can breed failure. Always focus on what the market wants, not what you think.

- Law of Failure – Failure is inevitable and part of the journey. Expect it and accept it. Recognize when you’ve made a mistake or failed, and cut your losses early.

- Law of Hype – “The situation is often the opposite of the way it appears in the press.” Things that are going well don’t need hype. “Revolutions don’t arrive at high noon with marching bands and coverage on the 6:00 P.M. news. Real revolutions arrive unannounced in the middle of the night and kind of sneak up on you.” “Forget the front page. If you’re looking for clues to the future, look in the back of the paper for those innocuous little stories.”

- Law of Acceleration – Long-term success isn’t built on fads; it’s built on trends. If you think you’re in a fad, one way to keep long-term demand high is to never fully satisfy the demand.

- Law of Resources – Marketing is a battle fought in the prospect’s mind. You need money to get into their mind and stay there. Marketers with money get more money because they have the resources to “drive their ideas into the mind.”

After reading this book, I thought about several marketing mistakes I’ve made. If I’d understood these laws, I would’ve made different decisions. If you’re like I was and could use a marketing-principles-for-dummies book, consider reading The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing.

New Books Added: Process Improvement, Russia, Fracking, and Enron Scandal

In 2024, I challenged myself to accelerate my learning by reading a book (usually a biography) a week. To date, I’ve done it for 80 consecutive weeks. I wanted to share what I was reading and also keep track for myself, which was difficult (see here), so I created a Library section on this site. I added to it all the books I’ve read since my book-a-week habit began in March 2024, and I’ve committed to adding my latest read to the Library every Sunday (see the latest here).

That left the books I’d read before 2024 unshared and untracked. I set a goal to add my old reading to the Library over time. It began with a Memorial Day Challenge to add five books (see here) and continued by challenging myself to add two books every weekend until my backlog is gone. Quite recently (see here), I decided to up the pace so I can finish this project well before the holidays—and begin another one!

This past weekend was my sixteenth weekend, and I added four more books:

- The Goal by Eliyahu M Goldratt and Jeff Cox

- Red Notice by Bill Browder

- The Frackers by Gregory Zuckerman

- The Smartest Guys in the Room by Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind

That’s the latest update on my weekend goal. I hope that sharing these books will be of value.

This Week's Book: Charles Schwab – $60 Newsletter to $100B+ Investing Empire

Last week I shared that I read a biography of Joe Ricketts, founder of Ameritrade (see here). One of his main competitors—and the company that acquired Ameritrade in 2020, over a decade after Ricketts sold it—was Charles Schwab Corporation. I was intrigued and wanted to learn more about the discount brokerage model and the era that birthed the model, so I read the autobiography of Charles Schwab.

Invested describes sixty or so years of Schwab’s journey in his own words. Interestingly, what eventually became Charles Schwab Corporation started in 1962 as a biweekly investing newsletter called Investment Indicators. Annual subscriptions were $60, and at its peak it had about 3,000 subscribers. No money management, just overviews of the economy, insights on select growth stocks, and hypothetical portfolios.

This newsletter catered to independent investors who were smart and capable of making their own decisions. The understanding gained from serving this demographic formed the foundation for what Schwab built over the next sixty years: a place for individual investors to manage their own investing.

Schwab’s journey to build his namesake firm and amass a personal fortune worth over $10 billion had its share of ups and downs. He does a great job of describing each segment of his journey and how he navigated its specific challenges in detail. He also describes what it’s like to navigate multiple stock market crashes when you run a brokerage that makes money from stock trades (spoiler: volume dries up, the brokerage business gets hit hard).

The most interesting aspect of his journey to me was his position in the early 1970s, when he was in his mid-30s. He described himself as “floundering.” He had zero assets and lots of debt. He was recently divorced, had young kids, and was living in a one-bedroom apartment while still trying to build his then floundering firm. Close to giving up, he began attending evening law school classes. But he pushed through and, with some lucky breaks in 1975, had a vision for a new model for individual investors, the discount brokerage.

I’m super interested in understanding the 1968–1982 era, and this book provided another great entrepreneurial perspective of the era and how to navigate challenging macro times.

If you’re interested in learning about Charles Schwab, Charles Schwab Corporation, the asset management industry, or how a nontechnical founder built what I consider a tech company, consider reading Invested.

New Books Added: $5B 1MDB Scandal and High-Stakes Underground Poker

In 2024, I challenged myself to accelerate my learning by reading a book (usually a biography) a week. To date, I’ve done it for 79 consecutive weeks. I wanted to share what I was reading and also keep track for myself, which was difficult (see here), so I created a Library section on this site. I added to it all the books I’ve read since my book-a-week habit began in March 2024, and I’ve committed to adding my latest read to the Library every Sunday (see the latest here).

That left the books I’d read before 2024 unshared and untracked. I set a goal to add my old reading to the Library over time. It began with a Memorial Day Challenge to add five books (see here) and continued by challenging myself to add two books every weekend until my backlog is gone. This past weekend was my fifteenth weekend, and I added two more books:

- Billion Dollar Whale by Bradley Hope and Tom Wright

- Molly’s Game by Molly Bloom

That’s the latest update on my weekend goal. I hope that sharing these books will be of value.

This Week’s Books: How Joe Ricketts Built Ameritrade and Disrupted Wall Street

Last week, I read about John Bogle’s journey to build Vanguard into an index-investing powerhouse (see here). That biography mentioned discount brokerages having been launched in the 1970s. Ameritrade was one of them, and I wanted to learn more about it, so I read the memoir of Joe Ricketts, founder of Ameritrade.

The Harder You Work, the Luckier You Get is a candid recount of Ricketts’s life in his own words. It details how he went from college dropout to struggling stockbroker with a growing family to founding his own discount brokerage firm in Omaha. Ricketts’s story was interesting because he didn’t found his firm (which ended up being a technology firm) near the financial capital, Wall Street, or the tech capital, San Francisco. He founded and scaled his firm in Omaha, Nebraska. Another thing that stood out to me was how regulation played a huge role in his success. In 1975, the government eliminated fixed commissions on stock trades, which opened the door to negotiated commissions and a new business model that Wall Street had never seen (and wasn’t ready for): discount brokerage. Ricketts and three partners launched First Omaha Securities, the predecessor to Ameritrade, that same year.

Ricketts’s early years were also interesting to me because they align with my interest in understanding the 1968–1982 era. Ricketts provides lots of perspective on this era and on how his firm navigated raging inflation and a bear stock market. A point Ricketts emphasized, and that I’ve read elsewhere, is that between 1968 and 1982, the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 75% of its value, adjusted for inflation (inflation peaked around 12%).

Anyone interested in learning more about Ricketts, Ameritrade, the stock brokerage business, or how a nontechnical founder built a tech company should consider reading The Harder You Work, the Luckier You Get.

New Books Added: Cocaine, Bitcoin Billions, Start-up Fraud, and the Silk Road

In 2024, I challenged myself to accelerate my learning by reading a book (usually a biography) a week. To date, I’ve done it for 78 consecutive weeks. I wanted to share what I was reading and also keep track for myself, which was difficult (see here), so I created a Library section on this site. I added to it all the books I’ve read since my book-a-week habit began in March 2024, and I’ve committed to adding my latest read to the Library every Sunday (see the latest here).

That left the books I’d read before 2024 unshared and untracked. I set a goal to add my old reading to the Library over time. It began with a Memorial Day Challenge to add five books (see here) and continued by challenging myself to add two books every weekend until my backlog is gone. This past weekend was a holiday weekend and my fourteenth weekend. I challenged myself a bit and added four more books instead of two:

- BLOW by Bruce Porter

- Bitcoin Billionaires by Ben Mezrich

- Bad Blood by John Carreyrou

- American Kingpin by Nick Bilton

That’s the latest update on my weekend goal. I hope that sharing these books will be of value.

This Week's Book: John Bogle and $10 Trillion Vanguard

A few months ago, I learned about a biography of John Bogle that describes how he created the index-investing revolution in America by building Vanguard. I didn’t read the book then, but when I heard that he started Vanguard in 1975, I got very interested because that’s in the 1968–1982 Nixon era I’m researching. Eric Balchunas, a senior ETF analyst at Bloomberg who wrote the book, also covers the topics of how Vanguard got into the ETF business and how the mechanics of ETFs work because he was curious about them.

The Bogle Effect is part biography and part history lesson on index investing. It details Bogle founding Vanguard as a way to save his job but then realizing the power of index investing and its potential impact on investors. Fees to buy or sell stock were high in those days, and Bogle’s decision to structure Vanguard as a company owned by the investors in its funds, not Bogle, was a game changer. It led to Vanguard disrupting the Wall Street fee structure, offering the cheapest index investing funds, amassing over $10.1 trillion in assets under management as of April 2025 (source), and employing 20,000 people. I was also interested to learn that even though Vanguard is the leader in index ETFs, Bogle wasn’t a fan of them.

This book gives a great overview of Bogle’s life and personality. It’s also an interesting education on the history of index investing and how it became such a big force in today’s stock market. Anyone interested in either of these should consider giving The Bogle Effect a read.

New Books Added: Twitter’s Origin Story, and How to Identify Your Unique Ability

In 2024, I challenged myself to accelerate my learning by reading a book (usually a biography) a week. To date, I’ve done it for 77 consecutive weeks. I wanted to share what I was reading and also keep track for myself, which was difficult (see here), so I created a Library section on this site. I added to it all the books I’ve read since my book-a-week habit began in March 2024, and I’ve committed to adding my latest read to the Library every Sunday (see the latest here).

That left the books I’d read before 2024 unshared and untracked. I set a goal to add my old reading to the Library over time. It began with a Memorial Day Challenge to add five books (see here) and continued by challenging myself to add two books every weekend until my backlog is gone. This past weekend was my thirteenth weekend, and I added two more books:

- Unique Ability by Catherine Nomura, Julia Waller, and Shannon Waller

- Hatching Twitter by Nick Bilton

That’s the latest update on my weekend goal. I hope that sharing these books will be of value.

This Week’s Book: The Real Cause of Every Tech Bubble

A few months ago, I was listening to The Slow Hunch podcast, on which the founders of the venture capital firm Union Square Ventures (USV) were interviewed. Fred Wilson and Brad Burnham are the founding partners; they shared stories of founding the firm and notable investments such as Twitter, Etsy, Cloudflare, and Coinbase.

Burnham mentioned a framework they used to develop their initial investment strategy. Where he and Wilson thought they were in the period’s technology cycle played a big role in their strategy. It led them to focus on investing in the application layer of the internet because, they realized, the infrastructure phase was behind them. They got this framework from a book Burnham had read. It had a profound impact on him and positioned USV to become one of the top investment firms by identifying the right founders and companies given their understanding of the technology cycle. You can listen to the sections of the interview where Brad talks about the book and how they used it here and here.

This piqued my interest and led to my booking that book, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital, by the Venezuelan economist Carlota Perez. The book is a blend of a history and a framework. It describes a way of thinking about cycles created by new technology and financial capital and analyzes the five major technology revolutions over the last 250 years and their implications for society: the industrial revolution; steam and railways; steel, electricity, and heavy engineering; oil, cars, and mass production; and information technology and telecommunications.

The core premise of this book is that the combination of new technology and financial capital applied to it creates a technology revolution that leads to speculative bubbles.

According to Perez, each technology cycle lasts roughly 50 years and follows a consistent evolution through three phases:

- Installation. New technology is created, and infrastructure is created to support it.

- Turning point. Speculators’ unrealistic expectations related to the new technology cause a recession or financial crisis.

- Deployment. New technology is distributed widely across society and is accepted, with new rules and regulations being implemented to avoid future crashes.

The book dives deep into the economic and societal impact of each phase, which I found very useful.

Anyone interested in understanding how long technology cycles work, how capital and new technology complement each other, or how speculative technology bubbles work should consider giving Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital a read. It’s dense and full of lots of material that will make you stop and think, so it isn’t a casual read. But Perez’s framing is especially helpful to me as I think about the current AI wave and where we likely are in the long AI cycle.

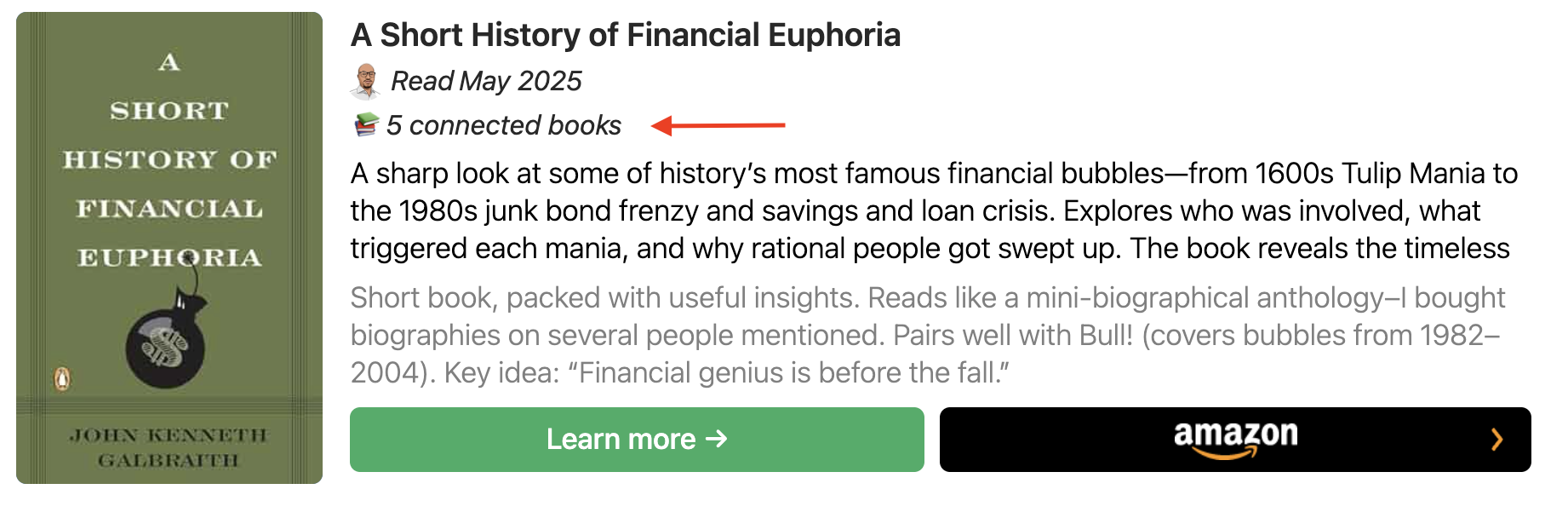

New: How Connected Is Each Book?

Books are connected to other books, but it’s not easy to see the connections unless you read an entire book. That makes how books are networked, or connected, invisible. The primary way I discover books is seeing them mentioned in another book. I’m constantly making mental connections of ideas, periods, events, or people mentioned in several books. This blog shows the connections between books, but it hasn’t been easy to understand how many connections a book has . . . until now.

Starting today, when you view the Library page, you’ll notice that next to each book is the number of other books in my library with a connection to it. It’s an easy way to quantify a book’s network. If the quantity of connected books is interesting, you can easily see each connection by clicking “Learn more” to see the book’s profile.

I’m excited about this. I haven’t seen anything like it on other blogs. It’s helped me think more deeply about book connections. I hope that understanding how networked a book in my library is will help people find books they find useful.

If you want to see for yourself, check it out: