James Dyson Part 5: What I Learned

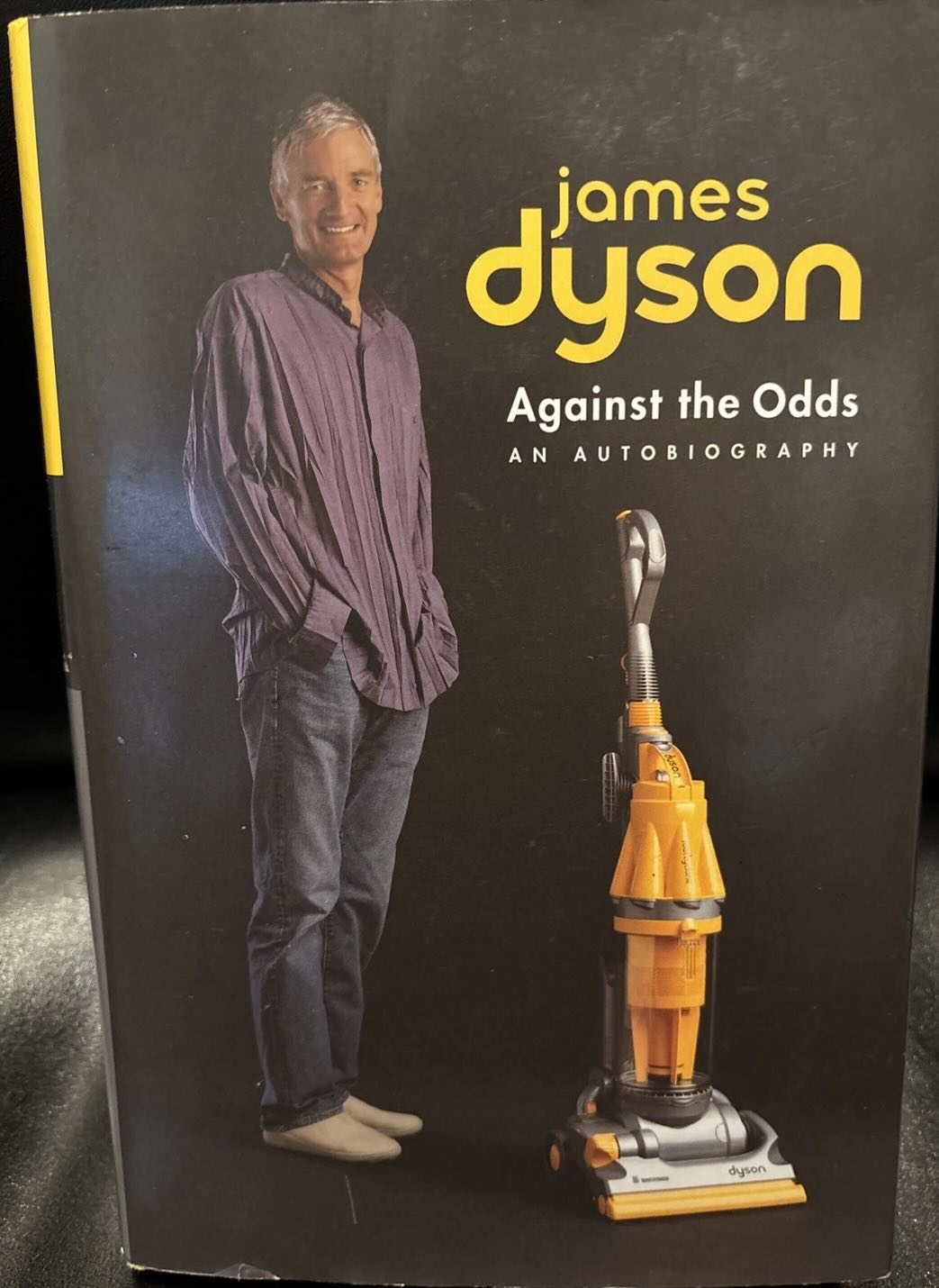

I finished reading about James Dyson’s journey. When his autobiography was published in 2003, James was 56 or so. Since then, James has continued building Dyson. As of this post, he’s 77 and appears to be still involved in Dyson, although he’s no longer CEO.

What Was James’s Starting Position in Life?

An entrepreneur’s early years often have a lifelong impact on them, and that was true of James. His father’s death when he was nine scarred him deeply. He didn’t have a father figure who could share knowledge with him. James felt like he had to figure things out on his own, so he learned to educate himself. He became a voracious learner, and he believes anyone can become an expert on any topic in six months.

His father’s passing also instilled in him a belief that he shouldn’t waste time doing things he doesn’t want to do. He learned to say no to things like medical school and leaned into things he was passionate about, like art, despite not having a clear path to where that passion would take him. In his early years, he believed that following his convictions would lead him to where he was supposed to be.

Two yardsticks that I use to evaluate entrepreneurs are distance traveled and personal velocity. James went further than most people will in a lifetime despite starting at a disadvantage. And his personal velocity, or the rate at which he moved toward personal goals, was exceptionally high and certainly increased his distance traveled.

How Did James Become Successful?

James’s wife, Deirdre, is a big reason he was successful. She supported him during the decade-plus when he traveled the world and the family was on the edge of financial ruin. When he was on the verge of quitting during the Amway lawsuit, Deirdre talked him off the ledge just in time for him to get a lucky break.

James is one of the most disciplined and focused entrepreneurs I’ve read about. For example, his ability to work for over 1,000 days straight, by himself, on a single product is a superhuman level of discipline, focus, and perseverance. He was clear on what he wanted and laser-focused on consistently taking small daily actions toward that goal. This led to his creating the technology that would be the foundation of his company. He moved a mountain by chipping away at it, one stone at a time, every day for years.

James was persistent but not stubborn. He knew he could build a big company around vacuums, but he was flexible on how he did it. His strategies evolved. For example, he started by licensing his technology but slowly moved to manufacturing his vacuum and selling directly to consumers as he encountered obstacles with license partners. He was rational in his decision-making. When he made a mistake, he acknowledged it and refocused his persistence on the correct actions instead of doubling down on his mistakes.

What Kind of Entrepreneur Is James?

James is a founder. He focuses on a problem and creates the best solution he can to solve it. He’s customer focused, not investor focused. He determines how to create the most value for the people who purchase his products.

James didn’t go straight to being a founder. Before founding Dyson on his own, he was an inventor. An employee of Jeremy Fry’s company. A cofounder of Dyson-Kirk with his brother-in-law. And a cofounder of Air Power Vacuum Company with Jeremy Fry. James wanted to reap the maximum reward for his efforts, and being a founder made that possible. This is likely why he still owns 100% of Dyson.

What Did I Learn from James’s Journey?

Licensing is a capital-efficient business model that I don’t have experience with. Licenses were a good way for James to generate recurring cash flows, which he used to hire his team and build out his manufacturing and direct-to-consumer operations. But licensing has downsides. Getting the details of contracts right, aligning the incentives, and dealing only with reputable partners are crucial considerations. If you get these wrong, you may never see a cent.

Vacuum cleaners aren’t a sexy market, but they’re a large one because lots of people use them every day. The autobiography didn’t say the market was growing, contrary to what I often see when companies have outsize success. But because he made a product that was ten times better than the competition, he was able to grab market share from competitors. Significantly improving products or services people use daily is a path to a big business, but the product can’t be comparable to the competition. In a market that isn’t growing, it must be an order of magnitude better.

The outsize impact on James’s products of editorial reviews in magazines and newspapers caught my attention. I knew reviews were powerful; it’s why products from unknown brands can be top sellers on Amazon. James appears to have figured this out earlier than most consumer-product companies. He also figured out that anything an ad can accomplish, true journalism can do better.

James says when you make something, sell it yourself. James doesn’t believe marketing agencies have the time or desire to learn about your product in depth. They’re best at applying their all-purpose skill to selling more of what already exists, not innovative things.

I’m bad at marketing, so seeing that he mastered this area is encouraging and gives me hope that I can too.

James is an amazing founder. His autobiography is a detailed account of his struggles. Anyone frustrated or thinking about giving up can benefit from learning about his journey.

Prefer listening? Catch audio versions of these blog posts, with more context added, on Apple Podcasts here or Spotify here!